Thirty Scales for Cello (Two and Three Octaves)

Edited by: Deckert, Hans Erik

Purchase Options

Share On:

Deckert Thirty Scales for Cello

By Hans Erik Deckert

Title: Thirty Scales for Cello

Composer: Hans Erik Deckert

Instrument: Violoncello

Editor: Hans Erik Deckert

Instrumentation: Technique

Pages: 8

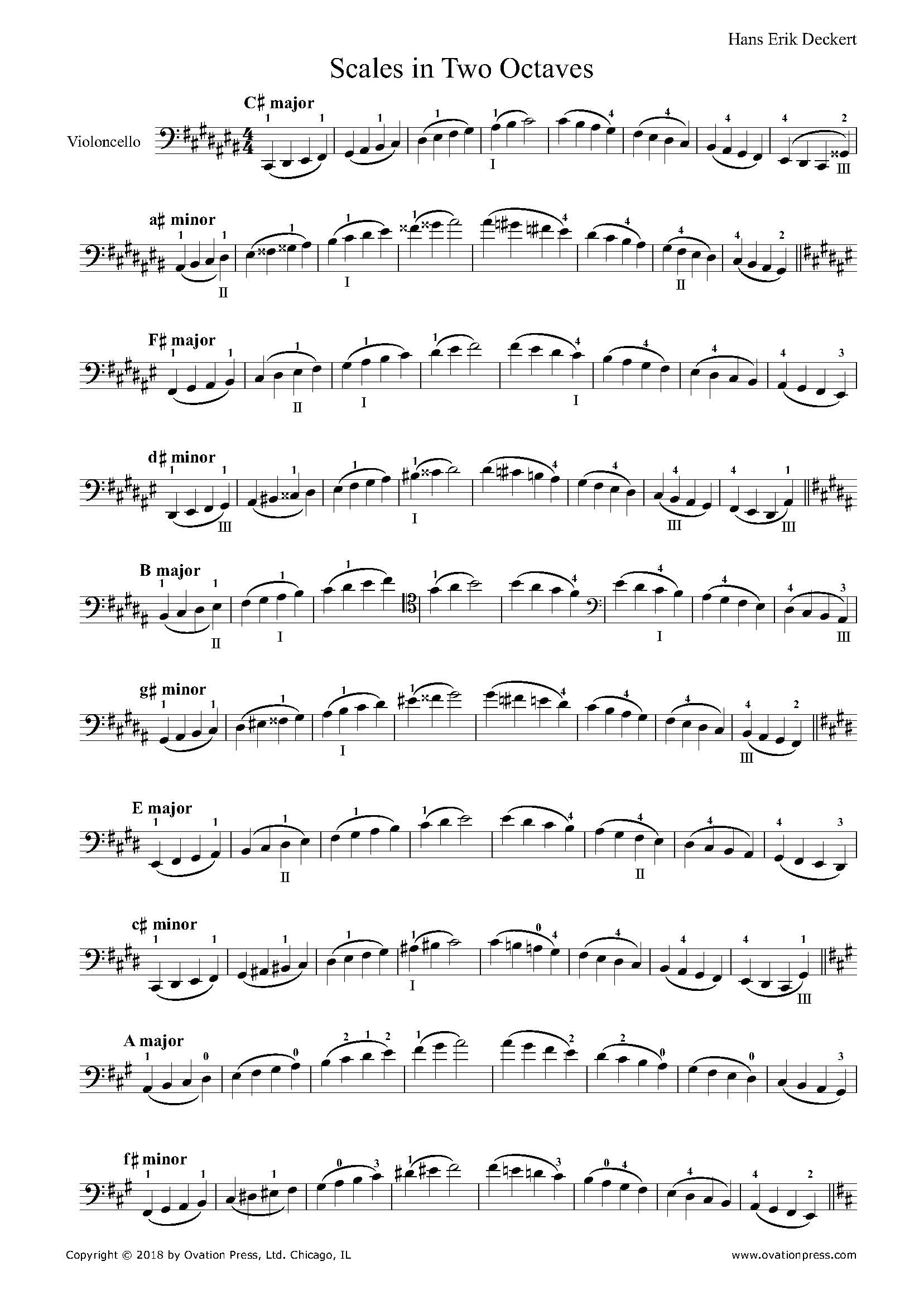

These scales, starting with C sharp major and ending on A flat minor are to be performed without stopping as this is the main goal of the exercise. Why 30 scales one might ask? Six scales from the total of the 24 are enharmonic variants:

- C sharp major - D flat major

- A sharp minor - B flat minor

- F sharp major - G flat major

- D sharp minor - E flat minor

- B major - C flat major

- G sharp minor - A flat minor

The above scales (with the exception of A sharp minor) are used widely in music.

The purpose of this study is to introduce scales with 4, 5, 6, or even 7 key signatures (which often are neglected), to improve security of finger patterns, and to widen tone variety.

In comparison to the C major scale, a similar finger pattern is used in the C flat major and the C sharp major (both a semi-tone lower and higher, respectively) - a very good reason to bring awareness to their importance in order to nurture intonation and good tone quality in a spectrum of different keys.

The above technical benefits of this are far from the real aim.

Deeper musical understanding must prompt us to further the inner musical feelings and in all keys.

What do E flat, C, A or F sharp majors mean as a musical reality? The same applies to minor scales.

Different musical experiences can be found in:

- C major in ‘Jupiter’ Symphony (Mozart);

- D minor in Quartet ‘The Death and the Maiden’ (Schubert);

- G flat major in Adagio from String Quintet in F major (Bruckner);

- F sharp major in Largo from String Quartet in D major Op.76 No.5 (Haydn);

- D flat major in Largo from ‘The New World Symphony’ (Dvorak);

- C minor in the 2nd movement (Marcia funebre) from Beethoven’s 3rd Symphony

In Schubert’s String Quintet in C we find 19 different keys.

In the Introduction (Le Malinconia) of the last movement - Quartet Op.18, No.6 (Beethoven) - 12 minor keys are found in fewer bars!

Why is the above mentioned Haydn’s Largo in F sharp and not in G flat major?

Why is Bruckner’s Adagio in G flat major and not in F sharp major?

In ‘Sigfried’s Idyll’ (Wagner), bar 71, the key is E sharp and not F major.

This phenomenon underlines the importance of the use of sharps and flats - a polarity of light and dark, extrovert and introvert differences.

The 30 scales are connected by reversed ‘mediant modulation’. After a major key, a relative minor follows with a modulation to the subdominant of the previous major scale.

Following this order, we begin with C sharp major and end on A flat minor.

The final enharmonic notes - G sharp and C sharp - lead again to the beginning. The last note in every scale builds a transition to the following one (supertonic, leading note).

Naturally, this order must be approached with great musical awareness.

All the scales can be played in two or three octaves. The beginning of each scale is to be played with relatively little emphasis. Time signature, rhythm, articulation, bowings, and fingerings, can be chosen freely. The melodic structure of the scales is to be treated as a starting point. An improvised piano part can re-enforce and enhance the changing nature of tonality. Tempo and dynamics should be moderate at first. It is also a good idea to apply this method to arpeggios.

Why do we practice scales? Because the scale is a ‘cell’ of melody - the first musical element we experience. Step by step we are moving upwards from the tonic towards the octave and back again to the tonic. Every degree of the scale has a different feeling and tension. What are the roles of the second, third, fourth, fifth, six, and seventh degree - also being the leading tone - and finally the octave? These are all different stages of one musical process.

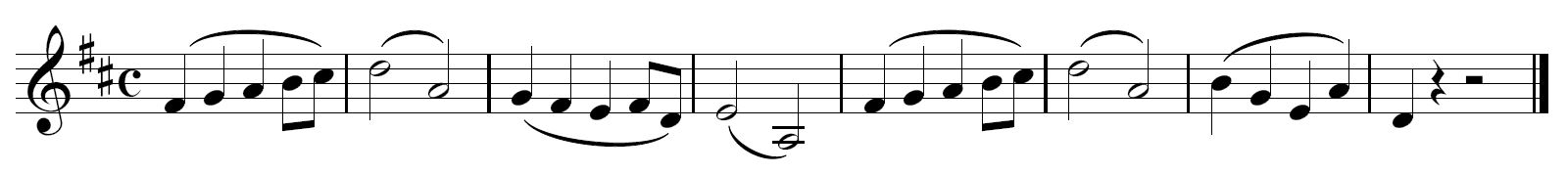

A perfect example of this is the second theme from Beethoven’s Violin Concerto:

The unforgettable violinist Isaac Stern said, “How is it possible that Beethoven takes six notes out of a scale and creates the most heavenly melody ever written?”

The melody, in D major, starts with a ‘sparkling’ F sharp (a third) and climbs to the octave (a final degree of the scale). Following that, it returns to A (a fifth and a dominant). An ascending and descending ‘journey’ in a space of 4 bars.

In the fifth bar the same repeats, but this time with the culmination continuing until B natural in bar 7 (third of the subdominant) then finally resting on D (bar 8).

Understandably, we must practice the technical demands of scales as well. Without this basic foundation we would not be able to experience ‘musical miracles’.

The undesired way to perform scales is with the correct notes yet in an indifferent and unmusical way. The main priority here is to present a ‘resurrection’ of this musical structure. Scales are much more than a technical warm up exercise. The purpose of the above study is to reclaim recognition and appreciation of this very important musical ‘cell’.

-Hans Erik Deckert